Reviving the Nineteenth Century 68mm Films with the Latest Digital Technologies

- Paulina Reizi

The Mutoscope and Biograph 68mm film collection, held at the Eye Filmmuseum in Amsterdam, The Netherlands, is an inseparable part of the global cinema heritage. These one-minute films from 120 years ago both fascinate film archivists and pose preservation challenges due to their unique content and technical particularity. The rich moving images capture fleeting moments from the turn of the 20th century and in terms of image quality, the information-carrying capacity of these wide-gauge films is estimated to correspond to 8–16K resolution in digital data. However, the best available projection in modern cinema theatres is currently a maximum of 4K quality.Citation: According to the Digital Cinema Initiative (DCI), a group of motion picture studios that developed the digital cinema resolution standards, “2K” means 2,048 pixels of horizontal resolution and “4K” means 4,096 horizontal pixels. Therefore, “8K” digital cinema would be equivalent to 8,192 pixels of horizontal resolution and “16K” means 16,384 horizontal pixels. Vertical resolution is not stated here, because it can be calculated from the aspect ratio. See https://www.dcimovies.com/ Furthermore, contemporary scanners cannot be used for obsolete archival material like the 68mm films, because of the films’ vulnerability and odd format (no perforations, unusual width). The Eye Filmmuseum and the British Film Institute (BFI) have been looking for alternative ways to preserve the characteristics of large films in digital format and introduced a new solution to reconnect these films to contemporary audiences.

In this article, I first discuss the significance of this film collection and the efforts in preserving it. I then investigate the questions raised during the first attempts of preserving and presenting these large-format motion pictures within the paradigm shift of digital practice in visual culture. In the wider field of film heritage practice, this case study of digitally reproducing obsolete analog films highlights relevant issues of sustainable film preservation and of access to our earliest film history.

Historical Context and Technology of the Collection

William Kennedy-Laurie Dickson (1860–1935), a Scottish motion-picture pioneer born in France, worked as an inventor, producer, and filmmaker under the employment of Thomas Edison from 1883 to 1895.Citation: For more information on the work of William Kennedy-Laurie Dickson, refer to Hendricks, G. 1964. Beginnings of the Biograph; The Story of the Invention of the Mutoscope and the Biograph and Their Supplying Camera. New York: Theodore Gaus' Sons Inc. McKernan, L. and van den Temple, M. (eds.). 2000. Journal of Film History Griffithiana: The Wonders of the Biograph, 66/70 (1999/2000). Sacile: La Cineteca del Friuli. Spehr, P. (2008). The Man Who Made Movies: W. K. L. Dickson. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. He is, in particular, notable for directing, producing, and featuring in one of the earliest films, created in 1891, Dickson Greeting.Citation: “[Dickson greeting],” Library of Congress. Accessed October 30, 2020. https://www.loc.gov/item/00694118/ After leading the development of the 35mm Kinetoscope for Edison’s company, Dickson, together with Elias Koopman, Harry Marvin, and Herman Casler, created in 1895 the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company. This film production company first focused on the development of the Mutoscope, a hand-cranked arcade machine using flipped paper-print cards for individual viewing, but due to new market prospects in cinema viewing and to avoid using Edison’s patented 35mm film stock, Dickson and his associates created a new projector, the Biograph. By recreating the same process but using a 68mm film stock, Dickson did not violate Edison’s patent rights and, in addition, offered a new technology with larger and sharper images.

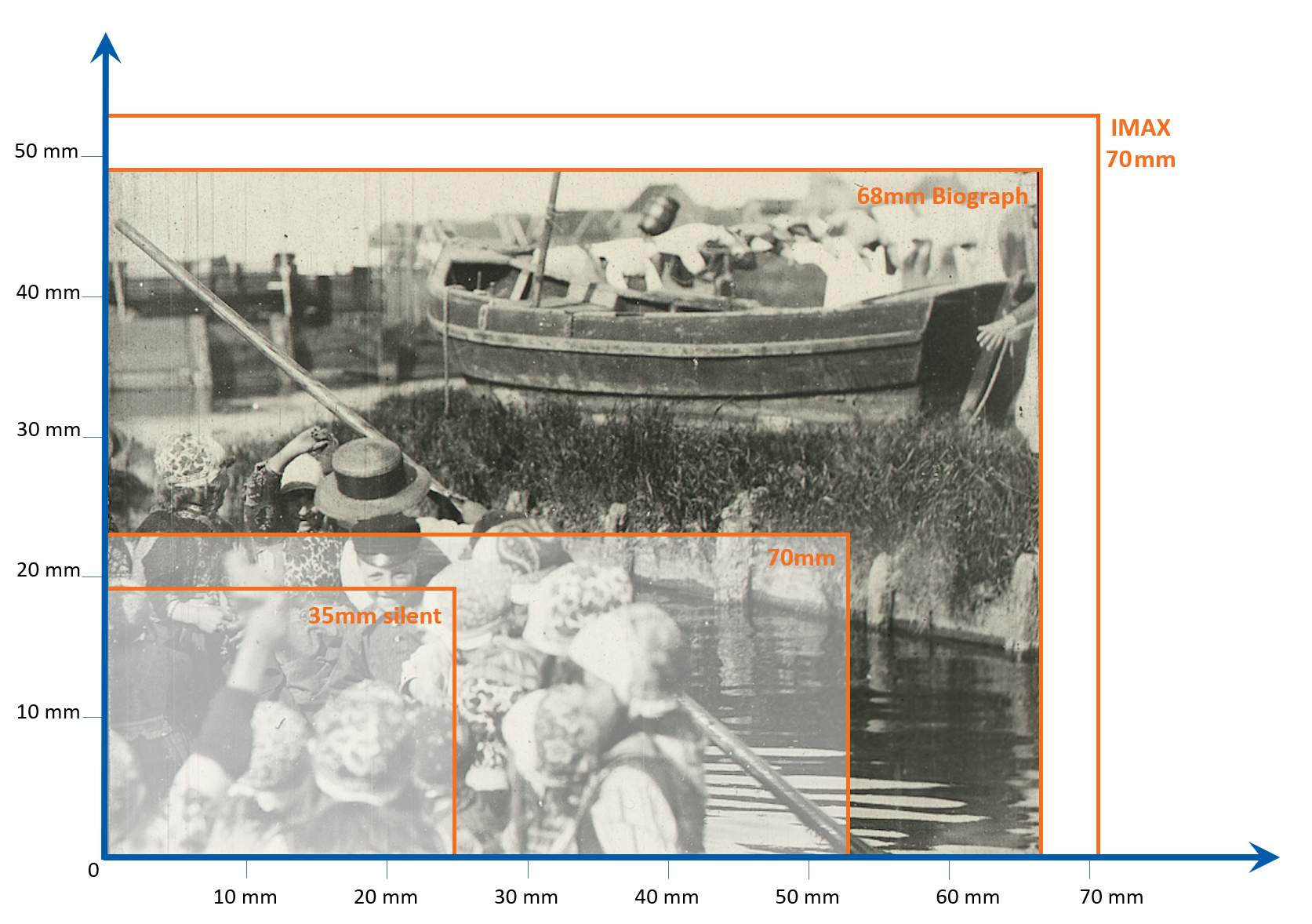

This new exceptional product offered a film format of approximately 2.75 inches wide and 2 inches high, also commonly referred to today as 68mm. To give an idea of its size, the image of a 35mm silent film frame would fit more than seven times in a 68mm frame (see the end note and Figure 2 comparing film formats).Citation: Specifications of indicative film format dimensions: (a) 35mm full (silent) camera aperture: 0.98” x 0.735”; (b) 35mm Academy aperture: 0.868” x 0.631”; (c) 65/70mm camera aperture: 2,072” x 0,906”; (d) 68mm camera aperture: 2.625” x 1.938”; and (e) IMAX 15-perf/70mm camera aperture: 2.772” x 2.072”. Unlike other formats, the negative 68mm film has no perforations on the sides of the image but only two perforations between successive frames and the positive copies have no perforations. With the image covering as large an area of the film stock as possible, it is extremely high resolution, providing extraordinarily rich detail. Furthermore, the camera’s high speed of filming gave clarity and brightness to the image.Citation: Rossell, 105.

On 14 September 1896, the 68mm Biograph premiered at Alvin Theater in Pittsburgh.Citation: The first Biograph (test) projection on a screen was in November 1895, according to the testimonies given in support of the patent acquisition. This exhibition took place in a machine shop in Canastota, New York, with the equipment located inside the shop and the lens pointing to a screen outside in order to test the machine capabilities. See Hendricks, 23–24. Newspaper articles reported on the remarkable novel technology and reception of an applauding audience, with The Post stating “The biographe (sic) shows a picture nearly twice as large as the similar machines in the other houses, and the impression is clear-cut and distinct.”Citation: Quoted in Hendricks, 40. The Commercial Gazette commented “Mr. Jefferson’s lips moved so naturally that one could almost imagine he heard the words that he seemed to utter.”Citation: Ibid. The Biograph was evidently not the first projector, but its capacity to project such large and sharp moving images on the big screen made a sensation. Right at the fall of the individual viewing machines and the rise of new technologies enabling better optics and reproducible film stock, the Mutoscope and Biograph company focused on theatrical projection of moving pictures and became a rival to Edison’s company.

Since the audiences were receptive to the Biograph, the content development went hand in hand with the technological one and creativity for the production of new material was stimulated. Starting in the United States with significant films, such as the presidential campaign of William McKinley at the end of 1896 (probably the first American political campaign on film), the company expanded across the Atlantic. In 1897, the first European affiliate was established in London and several others followed in places like Paris and Amsterdam. Paul Spehr has argued that this was the most effective film company in the world.Citation: Spehr 2007, 147. These national branches supported local film productions and also served as outlets for regional business deals to circulate the company’s offerings internationally.

Biograph camera crews were sent to several countries to capture short clips reporting on news events, such as royal family affairs, the Pope, the Boer War and city fires, as well as beautiful pictures that could captivate audiences, touristic landscapes, exotic animals, and comedies, but also some daily life scenes, dancers, or children playing. The significance was not in having a strong narrative of a feature-length film, but about the experience of enjoying the moving images. One could argue that these were similar to today’s YouTube clips.

Mainly because of the complexity of the projection system compared to the 35mm competitors, the production of 68mm Biograph films was discontinued in 1903.Citation: Spehr 2000, 51.

Surviving 68mm Biograph Films and Apparatus in the World

From the estimated 5.000 titles produced in 68mm between 1896–1903,Citation: Barry, “The Biograph Collections in Amsterdam and London,” 260. only few are known to survive today. The Museum of Modern Art of New York (MOMA) made an acquisition in 1939 from remnants of the Biograph company and within this material, 36 reels of 68mm as well as correspondence and production documentation tell the history of the company.Citation: Kehr D. “The First Movies,” MOMA, May 27, 2019. Accessed September 26, 2020. https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/70 The original 68mm Biograph films preserved in Europe include five films of the Will Day collectionCitation: van den Tempel, 235. at the Centre national du cinéma et de l’image animée (CNC) in France, nearly 100 titles of the Rolf Schultze collectionCitation: McKernan, L. “Big.” October 18, 2018. Accessed September 26, 2020. https://lukemckernan.com/2018/10/18/big/ at the British Film Institute (BFI), and the largest surviving collection of 200 titles belongs to Eye Filmmuseum in Amsterdam.

It is also interesting to note that there is very limited remaining associated equipment that would enable researchers to gain a better understanding of this remarkable technology. Specifically, three 68mm cameras are part of the collections of La Cinémathèque française.Citation: For a detailed description of the only known remaining 68mm cameras, refer to the online catalogue of La Cinémathèque française. Three cameras survive with only one that seems to be complete, fitted with its original lens. “Catalogue des appareils cinématographiques de la cinémathèque française et du CNC.” Accessed September 26, 2020. https://www.cinematheque.fr/fr/catalogues/appareils/collection.html?search=68+mm Unfortunately, there is no known surviving projector. I have indications that a projector model attributed as 70mm at Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History is a 68mm Biograph projector from 1897, but due to COVID-19 the vaults remained inaccessible in 2020 and confirmation (or not) of this hypothesis has to wait.Citation: Email exchanges with David Haberstich and Shannon Perich, curators of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, September 28–29 and December 14, 2020.

Eye Filmmuseum Mutoscope and Biograph Collection

The Mutoscope and Biograph collection contains the oldest films held by Eye Filmmuseum. It includes 225 nitrate film reels representing about 200 unique titles, with two hand-colored copies.Citation: Eye Filmmuseum. “Collection Eye.” Accessed September 26, 2020. http://ce.ka.filmmuseum.nl/ The films were (re)discovered in 1948 at the storage of a Dutch newspaper, and Willy Mullens, documentary filmmaker and producer, retained the original 68mm copies.Citation: van den Temple, 225. Mullens copied some of the originals to 35mm film stock, created a compilation of these reduced copies, and even filmed a staged recreation of the event to present his findings to the Dutch audience.Citation: Uit de Oude Doos (NL, 1948). See https://www.eyefilm.nl/en/collection/film-history/film/uit-de-oude-doos

In 1959, the film collection was acquired by the Nederlands Filmmuseum (now, Eye Filmmuseum).Citation: Based on a 1959 acquisition list of Nederlands Filmmuseum (NFM) and the 1959 inventory list of material transported from Haghefilm to NFM. After years of passive preservation in the museum’s vaults, a complex restoration project in the 1990s brought these films back to the general audience by using contemporary analog technologies.Citation: Surowiec, 133–134. van den Temple, 227–230. A rostrum camera was used to capture the original 68mm images onto 35mm negative frame by frame, like animation films. In order to improve image stability, the film frames were projected on the wall to define reference points, which were matched frame after frame during capturing. Thanks to the preservation work funded by the European Lumière project, the 35mm copies presented in the 1990s sparked a surge of several publications and in-depth studies on the technology, filmmaking method, and remarkable content.Citation: See as an example the publication of Le Giornate del cinema Muto in Pordenone: McKernan and van den Temple, 2000.

Going Digital: From 68mm to 8K Moving Images

Until 2017, the original 68mm films and the reduction 35mm copies formed the only available preservation materials of the Eye collection. With the advancement in digital film scanning and financial resources thanks to Unlocking Film Heritage, the largest film digitization project in the United Kingdom,Citation: BFI. “Unlocking Film Heritage.” Accessed September 26, 2020. https://www2.bfi.org.uk/britain-on-film/unlocking-film-heritage the British Film Institute (BFI) undertook the digitization of their own smaller collection of 100 films. In the frame of this project, 16 titles from the Eye collection relevant to the British heritage were also selected for a joint digitization project of 68mm films for the first time in 8K. The digitization and restoration of the complete set of 116 films was performed by the renowned Haghefilm laboratory, in The Netherlands. The output of this digitization was aimed to be first screened under the theme of early British cinema, titled The Great Victorian Moving Picture Show.Citation: BFI. “The Great Victorian Moving Picture Show Review.” Accessed September 26, 2020. https://www2.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/sight-sound-magazine/reviews-recommendations/great-victorian-moving-picture-show-silent-bioscope-actualities-wkl-dickson-imax-screen The project intended to be across the three major archives that hold the 68mm material—BFI, MoMA and Eye—in a spirit of inter-archive collaboration and there has been considerable interaction and an exchange of knowledge, methodology and material across the three collections. Thanks to this project, these films from the turn of the 20th century became available for projection on an IMAX screen and allowed for research and development of film heritage restoration with recent available digital technology.

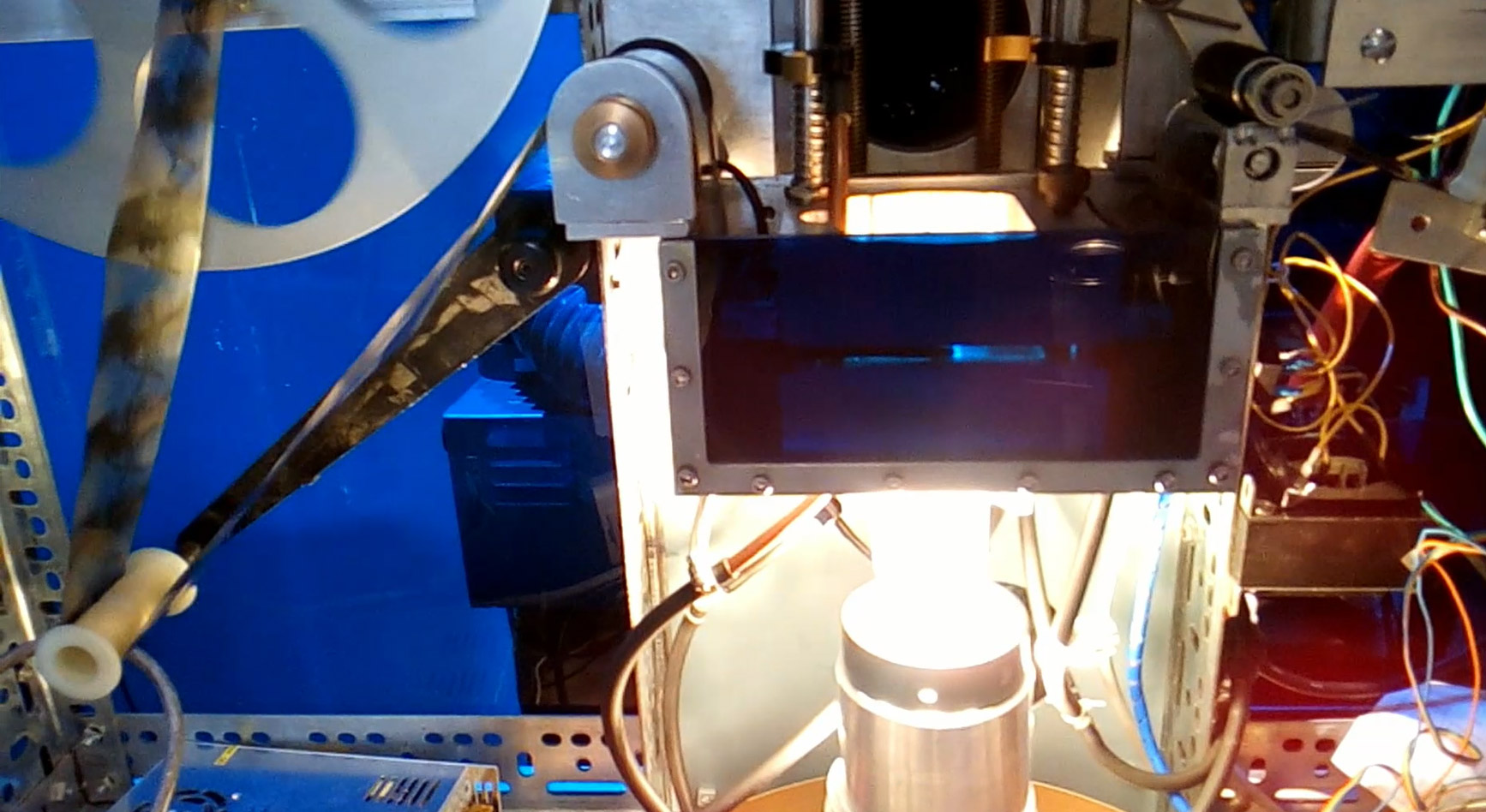

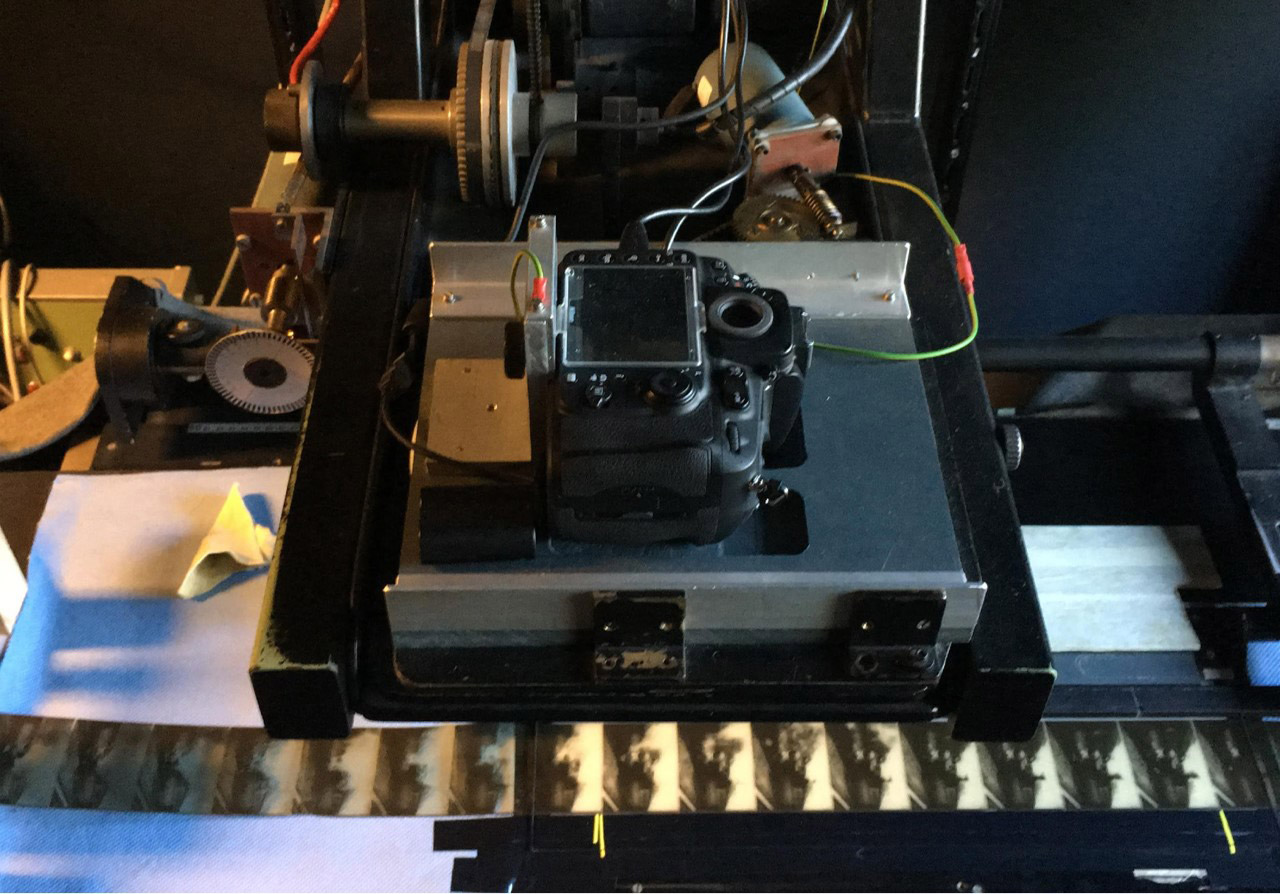

This innovative project combined a hybrid analog-digital workflow in order to produce the best possible digital and new reduction 35mm copies for theatrical presentation and preservation purposes.Citation: Bin Li, Film Restorer at Haghefilm Digitaal. Email exchange. December 2, 2020. A meticulous workflow has been designed to clean the analog films from leftovers of previous interventions and to capture the images digitally in around 8K resolution.Citation: The size of the final image was 7,360 x 4,912 with about 10% overscan. Ibid. Given the obsolete format, the digital workflow involved a rostrum camera that captured the images, frame by frame. In a similar manner to the analog customized scanning method employed in the 1990s, the camera would move horizontally above the 68mm film strip held down by a glass plate. At the end of each stretch of film, a new section would be repositioned and captured. The main difference was that the latest image capture was performed in 8K data instead of on a 35mm negative film. At the time (2018), a digital restoration at 8K was not technically feasible due to hardware and software limitations and the same constraints applied also to theatrical projection. Therefore, the digital restoration that included image stabilization and clean-up was carried out on downscaled 4K files. The restored 4K files became available for public viewing. The 8K copies enabled archivists to see how much can be achieved using new digital technologies and how the resolution/sharpness of our earliest moving images may compare with or even surpass the current digital capabilities.

The Brilliant Biograph

In 2019–2020, Eye Filmmuseum restored digitally 50 more film titles of its Biograph collection and invested in further research and development in film heritage practice, thanks to funding from the MEDIA program of the European Union.Citation: Eye Filmmuseum. “The Brilliant Biograph: Earliest Moving Images of Europe (1897-1902).” Accessed September, 26 2020. https://www.eyefilm.nl/en/film/the-brilliant-biograph-earliest-moving-images-of-europe-1897-1902?program_id=478163 This second digitization project allowed the combination of two different processes for scanning nonstandard archival films in 8K. About half of the films were scanned by Haghefilm Digitaal (Amsterdam) with the rostrum camera method described earlier. The other half were scanned at Cineric (New York and Lisbon) with a custom-made scanner equipped with a so-called “wet gate,” where the film is submerged into a liquid to reduce the visibility of superficial scratches. The choice of performing this parallel laboratory work was mainly done to gain time as it takes about one week to scan one film with the rostrum method.Citation: Frank Roumen, Director of Collections at Eye Filmmuseum. Interview. September 9, 2020. It also resulted in the creation of one more tool available to film archivists and the possibility of studying alternative restoration workflows to decide what can yield better results.

These successful attempts of digitizing some of the earliest moving images in the latest available technology raised several questions. Is it worth scanning archival films in such high resolution at the beginning of a restoration production chain, since they still cannot be projected unless they are downscaled? Could this process offer a sustainable long-term preservation output in case the original nitrate films deteriorate with time? And can the lessons learned from this work guide us to new effective approaches for preserving, accessing, and appreciating early cinema heritage?

Perspectives, Challenges, and Concluding Remarks

A workflow for 8K scan data allows for an optimal safeguarding of these films in the latest technology. This digital format can offer the highest fidelity to the original as a contingency in case the original films decay further. In contrast to fine art restoration in a traditional museological context, film restoration work pertains to basic repairs of the original film (e.g., cleaning, filling of superficial scratches) in an effort to minimize interference with the artifact, which is then duplicated to new copies for exhibition and preservation purposes. Any copy created through a film digitization/restoration project constitutes a new rendition, which is thus distant by at least one generation from the original analog film work. Yet, these digital renditions may serve in case the originals disintegrate completely or for reference purposes for later restoration work.

The high cost and associated computing and storage capacity of an 8K film preservation workflow continue to be a challenge. Compared to the approximate 75MB for a single frame at 4K, the increase to an equivalent 8K image of 300MB or moreCitation: DFT, “Scanity”, 12. is still problematic when it comes to computer handling and storage capabilities. For a 1-minute film of the Biograph collection, the storage required for the preservation files (in 8K) rounds up to 2TB.Citation: The preservation deliverables for one Biograph film include the 8K raw scans, the digitally restored files in DPX, DCDM, and DCP in 4K, and the proRes HD files. The preservation files are stored in LTO tapes in duplicate, according to best practices. To give an indication of the high volume, one hour of a 2K film (the resolution of typical current digital films) amounts to 1TB. Annike Kross, Film Restorer. Interview. November 25, 2020. The processing and storage capacity may presumably improve, but the costs can be challenging for smaller institutions.

The distribution of 8K films is currently limited to one TV station (NHK JapanCitation: NHK Japan is the first TV channel worldwide that broadcasts in 8K. See NHK, “About 8K.” Accessed September 26, 2020. https://www.nhk.or.jp/bs4k8k/eng/about8k/) and some online channels (e.g. YouTube), but new applications are steadily being developed and marketed. Similarly, even if it is not yet possible to project the 8K duplicates in cinema theatres, it is probably a matter of time to have such ultra-high-definition projectors. Looking further ahead, one can only imagine how the fast-evolving media technology might utilize the high-resolution digital moving images to create new experiences for the viewer. Thanks to the recent digitization projects, the newest technologies can be applied to the oldest surviving moving images in the coming years.

The advancements in high-resolution digital technology coincide with the accelerating minimization of screen size. These technologies are commonly used for individual virtual reality applications. The marketing that surrounds these new developments proposes an immersive viewing experience. It is striking to see how such arguments might have been used by Dickson and his associates when they promoted the peep-shows that initially displayed the films created by their new camera.

This case study is a stark reminder that moving image technologies evolve in a nonlinear manner, and not from primitive to progressively advanced. The 68mm case represents the most extreme span between the creation of a moving image object and its restoration with the latest technology. The restorations reintroduce the obsolete 68mm films to current audiences and invigorate new interest in early cinema techniques. This project shows that film archival material can still be revisited and restored more than a century after its creation, and that the preservation of originals can allow future technologies to generate new meanings and information.

Thanks to Giovanna Fossati, Frank Roumen, Anne Gant, Mark Paul Meyer, Annike Kross, Elif Rongen-Kaynakçi, Bryony Dixon, Bin Li, and Simon Lund.

About the Author

-

Paulina Reizi

Paulina Reizi is a film archivist at Eye Filmmuseum in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. She is a recent graduate of the MA programme in Preservation and Presentation of the Moving Image (P&P) at the University of Amsterdam. Paulina also holds an MSc in Information and Communication Technologies of Audio and Image and a BA in Journalism and Mass Communication from Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. She worked for over 10 years as a communications professional in organizations such as the European Space Agency, the United Nations, and the International Film Festival of Thessaloniki.

Notes

- According to the Digital Cinema Initiative (DCI), a group of motion picture studios that developed the digital cinema resolution standards, “2K” means 2,048 pixels of horizontal resolution and “4K” means 4,096 horizontal pixels. Therefore, “8K” digital cinema would be equivalent to 8,192 pixels of horizontal resolution and “16K” means 16,384 horizontal pixels. Vertical resolution is not stated here, because it can be calculated from the aspect ratio. See https://www.dcimovies.com/

- For more information on the work of William Kennedy-Laurie Dickson, refer to Hendricks, G. 1964. Beginnings of the Biograph; The Story of the Invention of the Mutoscope and the Biograph and Their Supplying Camera. New York: Theodore Gaus' Sons Inc. McKernan, L. and van den Temple, M. (eds.). 2000. Journal of Film History Griffithiana: The Wonders of the Biograph, 66/70 (1999/2000). Sacile: La Cineteca del Friuli. Spehr, P. (2008). The Man Who Made Movies: W. K. L. Dickson. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press.

- “[Dickson greeting],” Library of Congress. Accessed October 30, 2020. https://www.loc.gov/item/00694118/

- Specifications of indicative film format dimensions: (a) 35mm full (silent) camera aperture: 0.98” x 0.735”; (b) 35mm Academy aperture: 0.868” x 0.631”; (c) 65/70mm camera aperture: 2,072” x 0,906”; (d) 68mm camera aperture: 2.625” x 1.938”; and (e) IMAX 15-perf/70mm camera aperture: 2.772” x 2.072”.

- Rossell, 105.

- The first Biograph (test) projection on a screen was in November 1895, according to the testimonies given in support of the patent acquisition. This exhibition took place in a machine shop in Canastota, New York, with the equipment located inside the shop and the lens pointing to a screen outside in order to test the machine capabilities. See Hendricks, 23–24.

- Quoted in Hendricks, 40.

- Ibid.

- Spehr 2007, 147.

- Spehr 2000, 51.

- Barry, “The Biograph Collections in Amsterdam and London,” 260.

- Kehr D. “The First Movies,” MOMA, May 27, 2019. Accessed September 26, 2020. https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/70

- van den Tempel, 235.

- McKernan, L. “Big.” October 18, 2018. Accessed September 26, 2020. https://lukemckernan.com/2018/10/18/big/

- For a detailed description of the only known remaining 68mm cameras, refer to the online catalogue of La Cinémathèque française. Three cameras survive with only one that seems to be complete, fitted with its original lens. “Catalogue des appareils cinématographiques de la cinémathèque française et du CNC.” Accessed September 26, 2020. https://www.cinematheque.fr/fr/catalogues/appareils/collection.html?search=68+mm

- Email exchanges with David Haberstich and Shannon Perich, curators of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, September 28–29 and December 14, 2020.

- Eye Filmmuseum. “Collection Eye.” Accessed September 26, 2020. http://ce.ka.filmmuseum.nl/

- van den Temple, 225.

- Uit de Oude Doos (NL, 1948). See https://www.eyefilm.nl/en/collection/film-history/film/uit-de-oude-doos

- Based on a 1959 acquisition list of Nederlands Filmmuseum (NFM) and the 1959 inventory list of material transported from Haghefilm to NFM.

- Surowiec, 133–134. van den Temple, 227–230.

- See as an example the publication of Le Giornate del cinema Muto in Pordenone: McKernan and van den Temple, 2000.

- BFI. “Unlocking Film Heritage.” Accessed September 26, 2020. https://www2.bfi.org.uk/britain-on-film/unlocking-film-heritage

- BFI. “The Great Victorian Moving Picture Show Review.” Accessed September 26, 2020. https://www2.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/sight-sound-magazine/reviews-recommendations/great-victorian-moving-picture-show-silent-bioscope-actualities-wkl-dickson-imax-screen

- Bin Li, Film Restorer at Haghefilm Digitaal. Email exchange. December 2, 2020.

- The size of the final image was 7,360 x 4,912 with about 10% overscan. Ibid.

- Eye Filmmuseum. “The Brilliant Biograph: Earliest Moving Images of Europe (1897-1902).” Accessed September, 26 2020. https://www.eyefilm.nl/en/film/the-brilliant-biograph-earliest-moving-images-of-europe-1897-1902?program_id=478163

- Frank Roumen, Director of Collections at Eye Filmmuseum. Interview. September 9, 2020.

- DFT, “Scanity”, 12.

- The preservation deliverables for one Biograph film include the 8K raw scans, the digitally restored files in DPX, DCDM, and DCP in 4K, and the proRes HD files. The preservation files are stored in LTO tapes in duplicate, according to best practices. To give an indication of the high volume, one hour of a 2K film (the resolution of typical current digital films) amounts to 1TB. Annike Kross, Film Restorer. Interview. November 25, 2020.

- NHK Japan is the first TV channel worldwide that broadcasts in 8K. See NHK, “About 8K.” Accessed September 26, 2020. https://www.nhk.or.jp/bs4k8k/eng/about8k/

Bibliography

Barry, A. 1999/2000. “The Biograph Collections in Amsterdam and London.” Journal of Film History Griffithiana 66/70: 259–75.

DFT. “Scanity Multi Application Film Scanner White Paper.” Accessed September 26, 2020. https://www.dft-film.com/downloads/datasheets/Scanity-Whitepaper.pdf

Hendricks, G. 1964. Beginnings of the Biograph; The Story of the Invention of the Mutoscope and the Biograph and Their Supplying Camera. New York: Theodore Gaus' Sons Inc.

Kehr D. 2019.“The First Movies.” MOMA, May 27, 2019. Accessed September 26, 2020. https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/70

McKernan, L. 2018. “Big.” October 18, 2018. Accessed September 26, 2020. https://lukemckernan.com/2018/10/18/big/

McKernan, L. and van den Temple, M. (eds.). 2000. Journal of Film History Griffithiana: The Wonders of the Biograph 66/70 (1999/2000). Sacile: La Cineteca del Friuli.

Rossell, D. “The Biograph Large Format Technology.” Journal of Film History Griffithiana 66/70 (1999/2000): 78-115.

Spehr, P. C. 2008. The Man Who Made Movies: W. K. L. Dickson. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press.

Spehr, P. C. 2007. “Politics, Steam and Scopes; Marketing the Biograph.” Networks of Entertainment: Early Film Distribution 1895–1915. Kessler, F. and Verhoeff, N. (eds.), 147-56. Herts, UK: John Libbey Publishing Ltd.

Spehr, P. C. 1999/2000. “Throwing Pictures on a Screen: The Work of W.K.L. Dickson, Film Maker.” Journal of Film History Griffithiana 66/70: 11-65.

Surowiec, C. A. 1966. The Lumiere Project: The European Film Archives at the Crossroads. (Lisbon: Projecto Lumiere.)

van den Tempel, M. 1999/2000. “Making them Move Again: Preserving Mutoscope and Biograph.” Journal of Film History Griffithiana 66/70: 225–39.